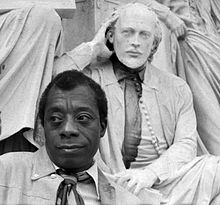

Mini Bio (1) James Baldwin was born on August 2, 1924 in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, New York, USA. He was a writer, known for I Am Not Your Negro (2016), If Beale Street Could Talk (2018) and American Playhouse (1980). He died on December 1, 1987. James Baldwin: A Biography Paperback – February 24, 2015 by David Leeming (Author) 4.8 out of 5 stars 630 ratings. See all formats and editions Hide other formats. List of the best James Baldwin books, ranked by voracious readers in the Ranker community. With commercial success and critical acclaim, there's no doubt that James Baldwin is one of the most popular authors of the last 100 years. One of the best African-American writers of all time, Baldwin's. An in depth and profound exploration of the complex writings and life of James Baldwin. An opportunity to clearly understand the layers of lies that have been built and embraced. James Arthur Baldwin, the son of Berdis Jones Baldwin and the stepson of David Baldwin, was born in Harlem, New York City, on August 2, 1924. He was the oldest of.

Who's the greatest American movie critic?

A lot of folks probably would say Pauline Kael or David Bordwell or Manny Farber; some might argue for more academic writers like Linda Williams, Stanley Cavell, or Carol Clover. For me, though, it's an easy question. The greatest film critic ever is James Baldwin.

Baldwin is generally celebrated for his novels and (as Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote recently) his personal essays. But he wrote criticism as well. Mostly this was in the form of short reviews. There is, though, a major exception: his book-length essay, The Devil Finds Work, one of the most powerful examples ever of how writing about art can, itself, be art.

Published in 1976, the piece can’t be categorized. It's a memoir of Baldwin's life watching, or influenced by, or next to cinema. It's a critique of the racial politics of American (and European) film. And it's a work of film theory, with Baldwin illuminating issues of gaze and identification in brief, lucid bursts. The dangerous appeal of cinema, he writes, can be to escape—'surrendering to the corroboration of one's fantasies as they are thrown back from the screen' And 'no one,” he acidly adds, “makes his escape personality black.'

The themes of race, film, and truth circle around one another throughout the essay's hundred pages, as Baldwin attempts to reconcile the cinema he loves, which represents the country he loves, with its duplicity and faithlessness. In one memorable description of the McCarthy era midway through the essay, he marvels at 'the slimy depths to which the bulk of white Americans allowed themselves to sink: noisily, gracelessly, flatulent and foul with patriotism.' It's clear Baldwin believes that description can often be applied to American cinema as well—whether it's the false self-congratulatory liberal Hollywood pap of The Heat of the Night or Guess Who's Coming to Dinner or the travesty made of Billie Holiday's life in Lady Sings the Blues, the script of which, Baldwin says, 'Is as empty as a banana peel, and as treacherous.'

Recommended Reading

Is James Baldwin America's Greatest Essayist? (Part One)

Is James Baldwin America's Greatest Essayist? (Part Two)

Your Moviegoing Experience Is About to Change

Shirley Li

Recommended Reading

Is James Baldwin America's Greatest Essayist? (Part One)

Is James Baldwin America's Greatest Essayist? (Part Two)

Your Moviegoing Experience Is About to Change

Shirley Li

Yet, for all its pessimism, The Devil Finds Work doesn't feel despairing or bleak. On the contrary, it's one of the most inspirational pieces of writing I've read. In part, that's because of the moments of value or meaning that Baldwin finds amid the dross—an image of Sidney Poitier's face in the Defiant Ones, which in its dignity and beauty shatters the rest of the film, or 'Joan Crawford's straight, narrow, and lonely back,' in the first film Baldwin remembers, and how he is 'fascinated by the movement on, and of, the screen, that movement which is something like the heaving and the swelling of the sea … and which is also something like the light which moves on, and especially beneath, the water.'

But more even than such isolated images, what makes the essay sing, and not sadly or in bitterness, is its sheer power of description, and its audacity in treating self, society, and art as a whole, to be argued with and lived with and loved all at once. You can see that perhaps most vividly in the concluding discussion, in which Baldwin talks about the racial subtext of The Exorcist.

For, I have seen the devil, by day and by night, and have seen him in you and in me: in the eyes of the cop and the sheriff and the deputy, the landlord, the housewife, the football player: in the eyes of some governors, presidents, wardens, in the eyes of some orphans, and in the eyes of my father, and in my mirror. It is that moment when no other human being is real for you, nor are you real for yourself. The devil has no need of any dogma—though he can use them all—nor does he need any historical justification, history being so largely his invention. He does not levitate beds, or fool around with little girls: we do.

The mindless and hysterical banality of evil presented in The Exorcist is the most terrifying thing about the film. The Americans should certainly know more about evil than that; if they pretend otherwise, they are lying, and any black man, and not only blacks—many, many others, including white children— can call them on this lie, he who has been treated as the devil recognizes the devil when they meet.

I like The Exorcist considerably more than Baldwin does, but even so, I think it's indisputable that he transforms the film. A pulp horror shocker becomes a meditation on how evil is displaced and denied—and on how denial of sin, personal and social, is central to evil. Baldwin's scorn doesn't destroy the movie, but turns it into something wiser, more moving, and more beautiful. As the blues that Baldwin loves changes sorrow into art, Baldwin takes American cinema and makes it look in the mirror to see, not the devil, but the face it could have if it were able to acknowledge its own history and violence. It's a face that would be, yes, blacker, but also more honest and more free.

In her first post at her blog at The Washington Post, Alyssa Rosenberg explained that she writes about pop culture because 'art and culture are deeply engaged with big, important ideas about the way we live our lives, the conditions we’re willing to let others live in and our most important priorities.' I don't disagree with that, and I doubt Baldwin would either. But I think The Devil Finds Work also makes a different case for writing about pop culture. That case is the case that Shakespeare makes for writing drama, or that Jane Austen makes for writing novels, or that Wallace Stevens makes for writing poetry, or Tarkovsky for making films. Baldwin shows that criticism is art, which means that it doesn't need a purpose or a rationale other than truth, or beauty, or keeping faith, or doing whatever it is we think art is trying to do. When I write about pop culture, I'm trying, and failing, to make art as great as The Devil Finds Work. That seems like reason enough.

Book links take you to Amazon. As an Amazon Associate I earn money from qualifying purchases.Publication Order of Standalone Novels

| Go Tell It on the Mountain | (1952) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| Giovanni's Room | (1956) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| Another Country | (1962) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| The Fire Next Time | (1963) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone | (1968) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| If Beale Street Could Talk | (1974) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| Little Man, Little Man | (1976) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| Just Above My Head | (1978) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

Publication Order of Short Story Collections

| Sonny's Blues | (1957) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| Going to Meet the Man | (1965) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| Jimmy's Blues | (1968) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| James Baldwin: Early Novels & Stories | (1998) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| Fifty Famous People | (2003) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| Vintage Baldwin | (2004) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

Publication Order of Plays

| The Amen Corner | (1954) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| Blues for Mister Charlie | (1961) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| One Day When I Was Lost | (1969) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

Publication Order of Non-Fiction Books

| Notes of a Native Son | (1955) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| Nobody Knows My Name | (1961) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| Black Anti Semitism And Jewish Racism | (1969) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| Harlem, U.S.A. | (1971) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| A Rap on Race | (1971) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| No Name in the Street | (1972) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| A Dialogue | (1973) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| The Devil Finds Work | (1976) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| The Price of the Ticket | (1985) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| The Evidence of Things Not Seen | (1985) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| Baldwin: Collected Essays | (1998) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| Native Sons | (2004) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

| The Cross of Redemption | (2011) | Amazon.de | Amazon.com |

James Baldwin was an American author well known for his novels, essays and poems. Baldwin wrote about everything from race to sex and class distinctions. The author’s works were well known for tackling complicated personal and social subjects in fictionalized settings.

+Biography

James Baldwin was born in Harlem in New York. Born in 1924, James was one of the first few African Americans that took a long and unflinching look at the issues of race and sex in the United States.

James’ mother, Emma Jones, left him in the dark about his biological father, refusing to even tell James his name. She raised him alone for a while before meeting and marrying David Baldwin, a Baptist Minister that James would come to call his father even in light of their strained relationship.

James Baldwin loved reading as a child. A student of DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, James took great pleasure in contributing to the institution’s magazine. It didn’t take long for James’ peers to recognize his talents, what with all the poems, short stories and plays he kept churning out as a young student.

It wasn’t merely his writing abilities that drew interest, though. James Baldwin showed that he could understand and manipulate sophisticated tools and devices of literature at a point in his life where most other authors would have been struggling to master punctuations.

James was intent on furthering his education through college. However, following his departure from high school in 1942, it became evident that the author’s family needed his help to stay afloat.

With seven siblings to worry about, James did whatever work came his way and it didn’t take him long to encounter worrying levels of discrimination. After losing his job and failing to find another, and losing his father, it became evident that James would have to change direction if he wanted to succeed.

Moving to Greenwich Village in New York City made sense to the author because the neighborhood had become a hub for artists. James wanted to write a novel. But he needed a way of supporting himself financially while he got his writing done.

After struggling through a couple of odd jobs, James was finally fortunate enough to get a couple of his essays and short stories published. James’ fortunes also included meeting a writer by the names of Richard Wright who got him a fellowship in 1945 through which James was able to support himself.

Even though he had begun making headway as a writer by this point in time, it wasn’t until James Baldwin moved to Paris that he garnered the freedom necessary to tackle the personal and social topics that he cared about.

James Baldwin Memoir Essays Examples

The author’s first novel, ‘Go Tell it on the Mountain’, delved into his personal life and struggles with his father and the religion he inherited. This paved the way for James to tackle homosexuality in another novel.

Though it wasn’t until the author began talking about race that his star began to shine. Through books like ‘Nobody Knows My Name’ and ‘Notes of a Native’s Son’, Baldwin explored the deplorable aspects of African American life in the United States.

James’ books added a voice to the Civil Rights Movement of his time and forced readers to explore the black experience as it was understood in that era. Where other black authors were content to moan about the horrors of life in the 20th century, James Baldwin went so far as to write essays aimed at the white community, designed to show them what it meant to be black.

James wasn’t bleak or fatalistic. His works challenged white readers to try looking at life through the eyes of their African American neighbors. He was always clear about his hopes and dreams for a brighter future. He endeavored to encourage the men and women who poured over his essays to work towards bringing the racial nightmare in the West to an end.

People who followed James Baldwin during his final years will tell you that his optimism did not last. By the 1970s, it was clear that the author was losing faith, primarily because of all the violence he witnessed, this including the assassinations of notable African American figures like Martin Luther King Junior and Malcolm X.

The strident tone in his later works was difficult to ignore. By the late 1980s, the author’s fame had waned and his presence was only felt in the occasional observations he made about America in popular publications.

James Baldwin died in 1987. He was 61 at the time, living in France.

+Adaptations

James Baldwin wrote a memoir featuring his recollections of the Civil rights Movement and its leaders. Titled ‘Remember this House’, James never finished the manuscript, though it was used in the creation of ‘I am Not Your Negro’, a documentary film released by Raoul Peck in 2016.

‘Go Tell it on the Mountain’ was turned into a movie in 1985.

+Go Tell It On the Mountain

This novel tells the story of a teenage boy who struggles to understand his place in the world in light of his status as the stepson of a Pentecostal Church Minister. The boy struggles with matters of a spiritual, moral and sexual nature.

This was James Baldwin’s first notable literary effort. He admitted that the book was autobiographical delving into his own experiences as a young boy trying to re-invent himself in a difficult world.

James Baldwin Books The Fire Next Time

The novel takes a hard look at an African American family and the manner in which it is impacted positively and negatively by religion.

+The Fire Next Time

This book was a bestseller when it hit the shelves back in the early 1960s. Rather short, the book constitutes two letters that speak to the black and the white community in America, urging them to overcome the legacy of racism.

This book is pretty harsh in the way it rebukes the American people, daring them to take a hard look at the consequences of emancipation and the manner in which the people of his country have squandered the freedoms they have been granted.

James Baldwin attacks the way Christianity was used to entrench racism; it is easy to see why some people might call this an angry book.

Book Series In Order » Authors »Leave a Reply

No Responses to “James Baldwin”

Comments are closed.